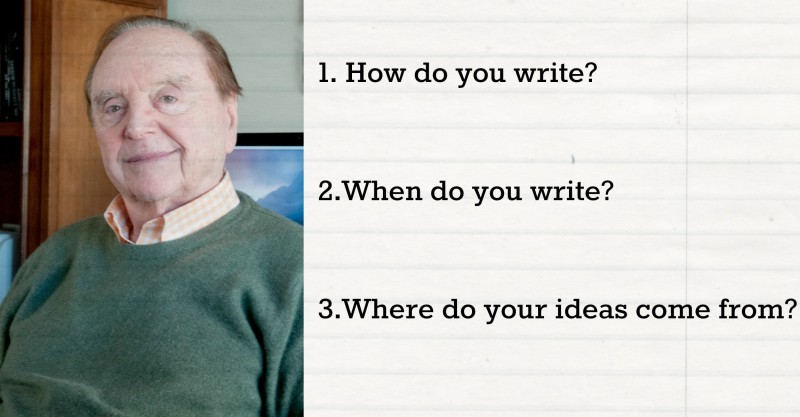

The 3 Questions for Authors

It is a strange phenomenon and most authors appear to confirm it. They are always asked the same three questions, whether the questions are asked in a formal interview setting or by readers, non-readers, fans, or casual acquaintances in every conceivable social setting. The three questions cross boundaries of country, language, age, and gender.

They are also always asked in exactly the same order. These are the questions:

How do you write? Meaning whether the author writes in long hand, typewriter or computer.

When do you write? Meaning time of day, morning, afternoons, or evenings.

Where do your ideas come from?

Although the repetitive pattern of these questions from all sources in this exact order is nothing short of uncanny, one can find some universal logic in the questions and their order. If one accepts the premise that writing a work of the imagination is an art form, whether fashioned as a novel, a short story, a play or a poem, then what the questioner is really asking is: How does one create the writer’s art?

One might pose this question as well to creators of the visual or musical arts.

The first two questions involve process and are easy to answer. But there is a long stretch between process and that crucial third question. This is the ultimate secret of the writer’s art. I do not want to sound mystical implying that these ideas are mysteriously channeled into the writer’s mind by some esoteric process of osmosis.

But the fact is that there is something unique about the ways in which ideas become stories that cannot be as easily explained as process. After all, a fiction writer creates a parallel world in his or her imagination. In creating this parallel world he or she deals with the single question that everyone must ponder. What happens next? Who among us does not want to know what happens next? It is the bedrock of all stories, lived or imagined.

Other Writers

For Proust, the aroma of a piece of cake inspired a vast tapestry of human folly and striving. For Tolstoy, a brief paragraph in a newspaper inspired the story of Anna Karenina. Hemingway found inspiration in the story of an old man’s struggle to land a big fish. Faulkner imagined a world inspired by life in a Mississippi County. It goes on and on. Every creator of a work of the imagination has some idea where his or her inspiration has come from.

While I can’t speak for every writer of fiction, my own experience tells me that most writers can identify the original spark that ignites the inspiration.

Nevertheless, these questions do reveal a clue to the people who ask it and why. They, too, have the urge to tell the stories that have been rattling around randomly in their brain. They want to extract the fiction writer’s explanation, hoping to find the magic key that will open the way to their own artistic creation.

It must be said at the outset that a committed novelist, like a prospector searching for gold, is always on the lookout for an idea that will spark a story. Every observation, every person he meets, every episode in their life, every thought, memory, reflection and cogitation is geared, consciously or subconsciously, to the concept of what will make a story. Everything in the zeitgeist was and is fair game.

Trans-Siberian Express and My Own Moment of Inspiration

For the record, I thought readers might like a sample answer to that third question, one that hardly can be articulated in a casual moment. Here is how I got the idea for one of my novels “Trans-Siberian Express”

I was having a drink in a Pub in London with a close friend, a British diplomat who was on leave from his post in the British Embassy in Peking in the mid seventies. It was at the height of the antagonism between China and the Soviet Union, and a hostile relationship existed between China and the West. I had met my friend years before in Washington where he was on assignment to the British Embassy in some capacity that he never defined, but which I intuited had some cloak and dagger aspect about it. I was a young soldier then, assigned to the Pentagon as the only Washington Correspondent for Armed Forces Press Service.

Since China in those days was a closed society, I was anxious to hear about his experiences in this world and, after a pint or two, he was happy to oblige. Then it came. The ignition spark. He described how he had periodically hand carried the Diplomatic pouch to Ulan Bator, the capital of Mongolia twice a month. He explained that his route was to take the railroad journey from Peking to Mongolia and explained how the Trans-Siberian Express was linked to this line and that he had taken it himself from Moscow.

As he described his journey on the Trans-Siberian Express, I became more and more intrigued. He told me it was the longest railroad trip in the world, a 7,000 mile journey through numerous time zones, that it’s original route was from Moscow to Vladivostok, the latter a naval base that was then off-limits to foreigners. He told me that the Russian track gauge was wider than the world standard, and the carriages had to be raised and the new wheels attached to ride the rails outside of the Soviet borders. He told me that sleeping compartments were assigned without regard to gender and that the food was ghastly and the third class passengers had to buy their food from vendors along the route through Siberia. He told me about the monotony of the Siberian tundra, the various ethnic groups that used the train as it traversed the route and that the train was pulled by giant steam locomotives, the largest in the world at the time.

One must relate this eureka moment to the context of the times and my world as a child growing up in the earlier part of the twentieth century. The train was the principal mode of land travel in those days. Railroad travel was exotic and far-reaching. The celebrity culture was built around trains and boats. Photographs of celebrities disembarking trains was a common media event. Railroad stations were palaces. Grand Central Station in New York City was a work of art, one of the most celebrated structures in the world.

Model trains were the ultimate toy for a boy and department stores featured elaborate displays to hawk these toys. Railroad travel was exotic and romantic and was featured in books and movies. Staterooms were shown as the height of luxury and private cars were the ultimate in luxurious travel. Graham Greene’s novel Stamboul Train and the movie The Lady Vanishes, among many others, offered exciting stories about train travel. I was a child of those times, and when my friend spun his yarn about his experiences on the largest train ride in the world, my head began to swim with story ideas. The idea had everything, Cold War intrigue, spies, staterooms assigned without regard to gender, the paranoia of the times, the closed world of the Soviet Union and China. The setting that filled my mind was a novelist’s dream, and my imagination began to conjure up a story that would take place around the centerpiece of a journey on the Trans-Siberian Express.

Ideas

Ideas for stories come from an amalgam of life experiences, observations, the chance meeting, an anecdote, a life changing personal experience like falling in love, being betrayed or abandoned, a memory of pain or loss, or joy and ecstasy.

They are triggered by books or newspapers, hearing stories told by friends, relatives or chance acquaintances, by movies or plays seen, songs heard, by incidents buried in one’s past or imagined. They come from dreams, visions, fantasies, memories, olfactory reminders, remembered tastes, traumas observed or experience, an errant look, a brief word, a religious experience.

What ignites your creativity?