Should We Believe the Myth of the Suicidal Writer?

Looking at the long list of writers who have committed suicide, one is tempted to associate the so-called artistic temperament, the agony of creative achievement, with the primary motivation for that final act.

The list is long and includes many well-known literary figures like Earnest Hemingway, Richard Brautigan, Louis Adamic, Romain Gary, Sylvia Plath, Arthur Koestler, Primo Levi, Ross Lockridge Jr., John Kennedy Toole, David Foster Wallace, Virginia Woolf, Jack London Stefan Zweig, Raymond Chandler and Hunter Thompson among others.

Those who tend to associate the internal struggles of the creative life with suicide often concoct reasons based on romantic, legendary assumptions that making art requires a private agony based on a God-given talent that forces its possessor to see and feel more than ordinary mortals.

The myth contends that because the artist is blessed with such extraordinary insight, he or she can see into deeper truths where there is only futility, darkness, disillusion and death. It is all part of the tortured artist stereotype.

I’m not entirely sold. Granted, the gift of talent is mysterious and for lack of better definitions, God-given or gene-driven. Its development and flowering requires grueling work, deep discipline and ferocious dedication.

Writers of fiction, of which I am a practitioner, spend a lot of time creating parallel worlds in which characters interact and pursue experiences that are activated within the mind. These worlds are based on the writer’s own experiences, hearsay and an amalgamation of memories, observations and ideas scrambling around in the imagination, all willfully whipped into order in a story format that seeks to find truth out of this muddle.

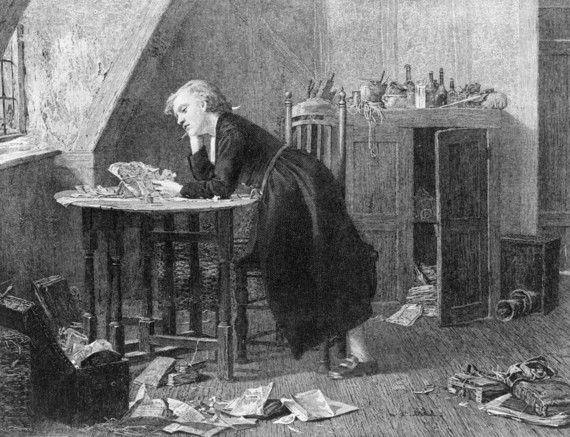

It is hard to convey the difficulties required to create fiction whether in the form of a novel, play or short story. It requires long hours of deep thinking and is a time-consuming and lonely effort of physical and mental labor to write and rewrite, ponder and argue with one’s muse on how best to render a story. It is, indeed, a profound exercise difficult to explain as a process except to like-minded people engaged in such a pursuit.

It’s easy to attribute a breakdown or a wish to escape from such a difficult and mysterious process. There have been many false romantic notions created by those who do not share these singular human talents. Some might conclude that one motive for suicide might be that the well has run dry, and the writer has reached the end of some mythical creative journey that has taken them to the edge of an equally mythical cliff, leaving the sole option of jumping into oblivion.

This so called “well run dry” theory has a long history and offers a satisfying explanation. It can’t be rejected completely. For writers and all artists, the creative impulse is the oxygen that sustains them, and the possibilities of its perceived loss is consequential and could very well spark end of life thoughts.

Then there is the theory of the failed writer, those who believe in their talent and creations, yet are repeatedly rejected and, out of frustration and failure, take their own life. John Kennedy Toole seems to be an example of that category. His literary recognition came after his suicide by his mother’s efforts to get his work published.

Perceived failure has long been a motive for suicide. But doesn’t that apply to anyonewho is unable to cope with unfulfilled dreams? Strangely, there is the case of Ross Lockridge, Jr. who authored the well-received novel Raintree County. Favorably compared to Gone With the Wind, it was made into a movie with the two reigning stars of the day, Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift. Any creative writer would consider this a home run. Not Mr. Lockridge. He shot himself on the eve of the movie’s release after the novel’s long run on the New York Times bestseller list.

But there are many wonderfully creative and successful writers, Shakespeare may be a pinnacle example, who seem to have decided to pack it in for other reasons. As they say, using the poker analogy, there is a time to hold and a time to fold.

The list of famous writers who chose the path of continuation of their creative efforts or simple retirement is far longer than those writers who snuffed out their lives through suicide, and many have engaged in a large spectrum of occupations and endeavors.

My own view is that the creative life offers both agony and ecstasy. Whether one is a writer, painter, composer or any other occupation where the gift of imaginary invention is required, one should accept their talent as a cause for celebration. The lucky possessor who discovers its power should accept the gift as long as it lasts. Sometimes it lasts a lifetime. Sometimes it flowers and wilts. As the poet Robert Herrick opines.

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today,

Tomorrow will be dying.The underlying causes of suicide are complex and numerous. It is a human fault line and is not exclusive to artists.